Cairo Entrepreneurship: Markets & People (Part 1)

This article is part of the #urbaneconomies series originally published on progrss and commissioned by district coworking space.

For the fourth and final installment of our #urbaneconomies series, we look at the dual role of markets and human capital in growing tech and non-tech entrepreneurship in Cairo, using Daniel Isenberg’s Domains of the Entrepreneurship Ecosystem as a guide.

With a potential of 90 million consumers, Egypt is an attractive market for any business. But in spite of its massive potential, entrepreneurs working on the ground find it difficult to penetrate large swathes of the market.

Based in San Francisco, Egyptian entrepreneur, investor and co-founder of Parlio Osman Ahmed Osman believes that Egypt’s potential as a market is often overstated. “Egypt is not that big of a market – the population is not that big and people don’t have that much disposable income. Entrepreneurs in Egypt have a policy of targeting the Middle East, and they end up falling in a trap, because it feels like the Middle East is this one homogeneous thing, but it’s really not – each country is culturally different, has a different legal landscape and demographics, so you have to figure out a strategy for each country, and then you lose the economies of scale,” he explains.

Others note that the dominance of the informal market and low banking penetration make it difficult for entrepreneurs to play by the rules. “The number of entrepreneurs who choose to go the way of the informal market means that we don’t have data, so we don’t know if they’re actually profitable. And because they don’t pay their dues, it makes it difficult for others to compete,” says Mohamed El Sawy, owner of The Courtyard and CEO of Misr Contracting Company.

“It’s very frustrating [to do business in Egypt] – not just amongst entrepreneurs and startups, but even amongst big businesses. Every day, you compete against someone whose cost is at least 10% lower than you – which means they make more profit. They are able to go through the system faster because they don’t have to abide by the laws,” he adds.

El Sawy notes that the dearth of data makes it very difficult for entrepreneurs – or investors, for that matter – to assess the actual potential of markets in Egypt. “Entrepreneurs pursue opportunities that are easy for them to carry out and that they have resources to achieve, as opposed to businesses that serve an actual need. Those are much more difficult to come by and they make less money,” he explains, noting that gatekeepers are often still required to penetrate the market in Cairo, which results in entrepreneurs pursuing opportunities where they have connections.

According to Dina Sherif, CEO and co-founder of Ahead of the Curve (ATC) and Associate Professor of Practice and Director of the Center for Entrepreneurship at the American

University in Cairo, one of the reasons that so many entrepreneurs turn to tech is ease of market access. Sherif, who was recently selected as a local Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) Pioneer by UN Global Compact, co-founded ATC in 2012 to promote sustainable management practices, inclusive market growth and innovation for societal well-being across the Arab world by supporting entrepreneurs and multinationals. Sherif explains that the ease of doing business online has made it attractive for many entrepreneurs to turn to tech. “In the online world, the barriers are minimal because there is no [need for personal connections] and there are no licenses, but if you want to build a factory or start a call center, you have to get a million and one approvals… So it’s a different setup and a different space,” she says.

Sherif – who perceives the dichotomy of tech and non-tech as redundant – believes that all business will be tech-enabled in one way or another in the next 10-20 years. For her, the market potential in Egypt remains huge, but the key is finding ways to penetrate marginalized communities that are ‘off the map.’ “We are yet to hear of a multinational that has left the Egyptian market, unless it has to do with strategic reasons. The issues that we need to fix have to do with ability to access products in different areas,” she adds.

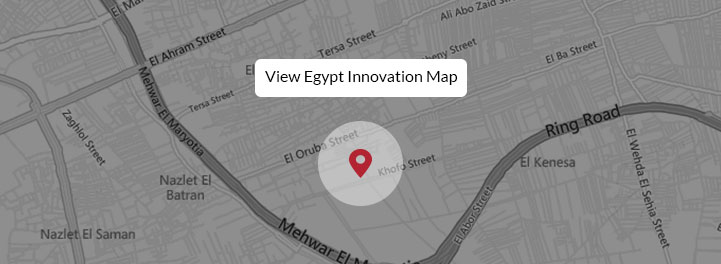

Egypt ranked 116 out of 140 countries surveyed for the WEF’s 2015-2016 Global Competitiveness Survey. Source: WEF Global Competitiveness Survey 2015-2016.

In the 2015-2016 WEF Global Competitiveness Report, Egypt ranked 116 out of 140 countries surveyed. And while pillars like Market Size ranked relatively well, scoring 5.1 out of a potential 7 points, others, like Higher Education and Training (3.2), Labor Market Efficiency (3.2), Business Sophistication (3.7), and Innovation (2.7) reflect some of the bigger challenges that business owners in Cairo face.

Stay tuned for part 2 of the fourth article in the #urbaneconomies series. This article is brought to you by:  and

and

EgyptInnovate site is not responsible for the content of the comments