Cairo: A Legacy of Entrepreneurship (Part 1)

This article is part of the #urbaneconomies series originally published on www.progrss.com and commissioned by district coworking space.

In the 1930s, a young boy of 11 fled his village to Cairo, only to become an apprentice to a foreign cobbler who made shoes for Egypt’s royal family. 20 years later, and in the aftermath of 1952 ousting of King Faruq, the shoemaker was forced to leave Egypt, leaving the young man – who had by then mastered the craft – with the capital’s most prestigious shoe workshop. But the young apprentice’s ambitions exceeded those of his master, and in 1954, he established Egypt’s first shoe factory; that man was Mohamed Lotfy, founder of Lotfy footwear. Over the course of this four-part series on entrepreneurship, we examine the factors that affect Cairene entrepreneurs, from access to markets and human capital to culture and support structures to finance and policy.

Although Talaat Harb is often credited with introducing entrepreneurship to Cairo with his founding of Banque Misr, Egyptian entrepreneurship has much deeper roots. In fact, since its founding in 973, Cairo was designed first and foremost as a commercial and manufacturing hub, with artisans and craftsmen clustering their businesses in various parts of the city. Today, those business clusters still exist, from the car-repair workshops of El Hirafiyyeen and the tile and marble manufacturers of Shaq El Tho’ban, to electronic equipment providers in Downtown’s El Bustan and the hustle of mobile and electronic accessories’ traders on Abdel-Aziz Street.

One of Cairo’s first known entrepreneurs, sixteenth-century Egyptian merchant Ismail Abu Taqiyya “…anticipat[ed] Starbucks by several centuries” by importing coffee to Egypt from Mocha in Yemen. Far from risk-averse, his choice to finance coffeehouses came at a time when coffee and coffeehouses were highly politicized, and when puritanical scholars perceived the drink as sinful. Abu Taqiyya also invested heavily in the sugar industry, and although he had a conglomerate that stretched from India to Nigeria during his lifetime, it fell apart after he died, leaving little of his innovative brand of entrepreneurship behind. And while there are traces of others like Abu Taqiyya, there is little to no record of them, making it almost impossible for historians to piece together the many stories of early Egyptian entrepreneurs.

But the kind of entrepreneurialism that was so inherent to Abu Taqiyya’s vision has waned over the years, and in spite of many similar examples of early entrepreneurialism, entrepreneurship remained largely absent from mainstream business language until very recently – although Cairo has no dearth of entrepreneurs, large and small. In the twentieth century, entrepreneurship among the middle class gave way first to the retirement-plan-guaranteed government jobs that were so popular between the 1950s and 1960s, and later, to large contracting businesses and clear-career-path multinational jobs that characterized post-Infitah neo-liberalism. On the ground, however, entrepreneurs like Abu Taqiyya continue to operate, although they – like their historical counterparts – remain largely invisible.

New Words, Old Practice

Today, innovators like Abu Taqiyya are considered entrepreneurs and their brand of entrepreneurship is referred to as riyyadit a’mal. And although a number of factors have compounded to bring entrepreneurship into a mainstream business language in Egypt, US President Barack Obama’s speech “A New Beginning” at Egypt’s Cairo University in 2009 is clearly one of the sparks. The summit that he promised to hold in 2009 has since become the annual Global Entrepreneurship Summit (GES) – the seventh edition of which is being held in Silicon Valley this June. Since then, the word riyyadat al-a’mal (which, although more familiar, still doesn’t quite roll off the tongue) has come to be closely associated with high-growth, tech-driven and innovation-driven entrepreneurship.

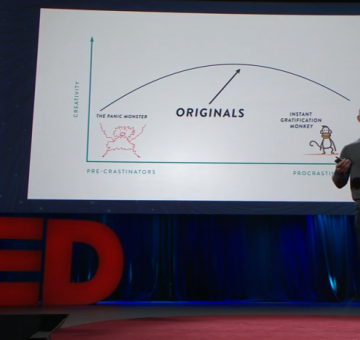

Besides the American president’s speech, other factors have contributed to making entrepreneurship more attractive to (particularly young) Egyptians. These include years of donor efforts; the after-effects of the global financial crisis; the compounding of efforts of various ecosystem players – including government, NGOs, and private sector; and a paradigm shift in perceptions of social norms (not to mention an interest in tech) that followed the outbreak of the 2011 revolution.

According to Assistant Professor and Abdul Latif Jameel Endowed Chair of Entrepreneurship and Director of the American University in Cairo’s Venture Lab Ayman Ismail, entrepreneurial startups come in various types, sizes and rates of growth. “For me, someone who opens a new business, be it a technology company, a small store, or a workshop is entrepreneurial. S/he is taking the initiative, assuming risks, and putting together the resources to build this new business. The business might grow and become a large retail chain or it might stay small for 50 years, this is more about the entrepreneurs’ choice and the market potential,” he says.

And while Ismail is proficient in his definition, interviews with 20 professionals working in business and entrepreneurial support industries failed to produce a single cohesive definition of entrepreneurship – partially a reflection of just how loose our understanding of the term is today.

Angel investor and serial entrepreneur Con O’Donnell has lived in Cairo for upwards of 20 years and is now based at the downtown GrEEK Campus – a tech hub established in what used the be the American University in Cairo by entrepreneur and co-founder of Sawari Ventures Ahmed El Alfy. In 2001, O’Donnell founded media startup Sarmady – which includes websites like filgoal.com, filfan.com, and filbalad.com – which he then sold to Vodafone in 2008. Today, he is part of the lead team at RiseUp Egypt, an annual summit that hosted over 4,000 attendees from 49 countries at the three-day event last year, and the GrEEK Campus’s concrete walls still bear RiseUp’s strong yellow paint when I meet him there.

As someone who has closely been closely involved in developing a culture around entrepreneurship in Cairo, O’Donnell is quick to admit that one of the biggest challenges is the inaccessibility of the language in general. “Some effort needs to be made to translate the language into plain English and then into plain Arabic. Some inroads have been made…but you want the muppets talking about it as well and that has to happen organically,” he says.

Stay tuned for part 2 of the first article in the #urbaneconomies series.

This article is brought to you by

EgyptInnovate site is not responsible for the content of the comments